In mid-March, I got email from a student at my alma mater, BITS Pilani (the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, in Pilani, Rajasthan). This is part of her message:

Respected Mr. Dilip D'Souza,

Greetings from BITS Pilani!

Every year, we organise the Think Again Conclave, our annual guest lecture series where we bring together distinguished leaders and visionaries from various fields to share their invaluable experiences and insights through engaging talks and guest lectures.

The Think Again Conclave has hosted eminent speakers such as Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam (former President of India), Vint Cerf (Father of the Internet), Jimmy Wales (founder of Wikipedia), Dr. John C. Mather (Nobel Laureate, Physics), Deepa Malik (India's first female Paralympic medallist), Nitin Gadkari (Union Cabinet Minister), and Sir Harold Kroto (Nobel Laureate, Chemistry).

We would love to host you, sir, as a distinguished speaker at this year’s Think Again Conclave. You can choose to speak on any topic or have the talk in an interactive manner, as per your comfort.

How could I say no? So I went to Pilani last Friday and spoke on Saturday afternoon. Below is what I said.

They think, therefore I am

Hello BITS Pilani, or maybe I should say Hello BITS Pilani Pilani campus! You do me a great honour by inviting me to speak today, and especially because it's you students who thought of me - that touches me somewhere very deep. I am, after all, just a run-of-the-mill EEE (Electronics and Electrical Engineering) graduate. In the 15 EEE courses I did here, I collected 11 Cs and 4 Ds. Worse, I've had nothing to do with EEE in all the years since I graduated. So you'd be right to wonder, why was I here at BITS at all? What did I learn here? Why am I here today?

I don't have good answers to those questions. So what I thought I'd do today is tell you about six moments in my life that said something to me, that I think about, that I learned from. And I'll let those moments speak for me.

1) The first was right here on this campus. My last semester at BITS, in 1980. Struggling to cope with EEE courses I had zero interest in, thinking I had some aptitude for mathematics, and entirely unaware what I was getting into, I signed up for an "Optional Free Elective" called "Combinatorial Mathematics". It was taught by the great VK, V Krishnamurthy.

He was a wonderful teacher, taking us with verve and passion on a tour through plenty of esoteric ideas. While I was constantly fascinated, I also found the course a constant struggle. But it was a struggle that, to my amazement, I relished. I ended with a B, but the hardest-earned B of my years here, the grade I am proudest of. And I also managed to earn VK's respect and friendship. It must have been the letter he wrote to recommend me that got me admission to a fine university the next year, for my grades here were, shall we just say, pathetic.

The reward, VK taught me, is in the struggle to understand.

2) In the mid-1980s, I lived in a town called Austin. I had a good job, a great set of friends, a handsome dog called Shaka, played tennis 3-4 times a week, basketball, Spanish lessons, went to little bars to listen to music ... all comfortable, easy.

Then one day, a friend called: "Where's the passion, Dilip?"

For other reasons, I promise you, he's no longer a friend. But the question stayed. Was everything always going to be easy and comfortable? Would I ever find a passion for something? Was it necessary?

I don't know if it was because of his question, but around that time, I began volunteering at a City of Austin programme, three evenings a week. These were classes for adults who had dropped out of high school and now wanted a high school diploma - or really, the equivalent.

Given BITS, and my degrees and profession, I signed up to teach mathematics and science. But I ended up teaching people to read. It boggled my mind that all these adults were driving to the classes - without being able to read a word of English!

Out of the blue at the end of that year, I got a letter from the City, saying I had been chosen as the Outstanding Volunteer for that year. And at a glittering ceremony some weeks later, the Mayor gave me a plaque and a citation that said I had "commitment, reliability and ability." It remains the award I'm proudest of. It answered some questions in my mind, about passion.

3) In those Austin years, I took Shotokan karate lessons. Just a small group of us, led by a genial black belt called Lee. Great emphasis on form, balance and mindset - and again, Lee was a wonderful teacher and mentor. Sadly, he died three years ago. I miss you, Lee.

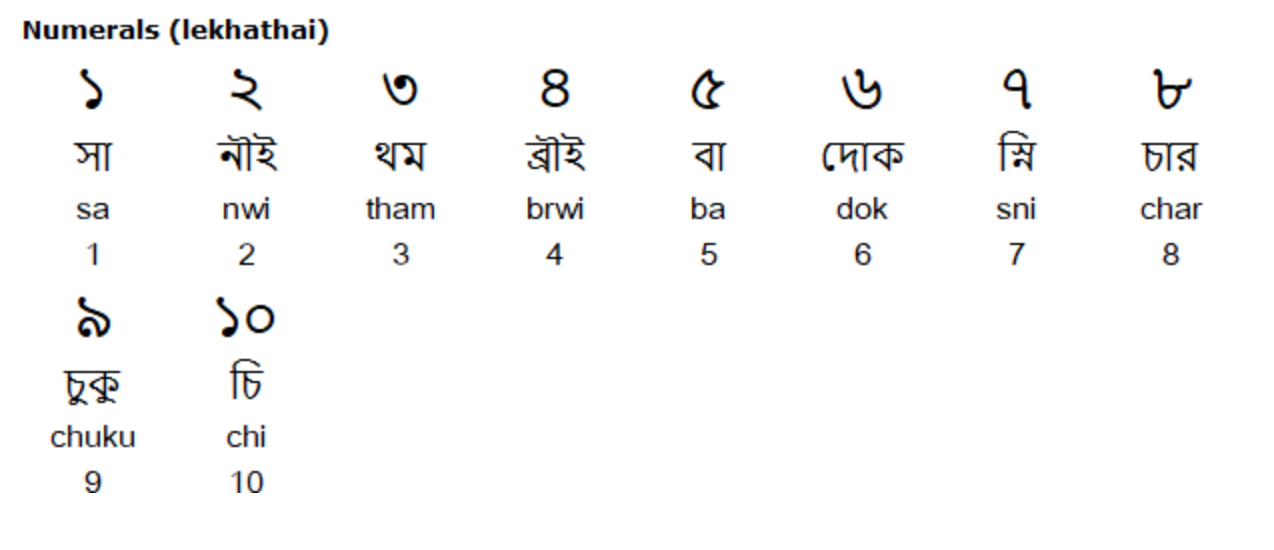

But I remember him most for the times he'd come to our session and announce, with no preamble, "Today we're doing 1000 mowashi-geri" (a particular roundhouse kick). And I'd think, "1000! How will I survive that?" But Lee gave us no time to think really. He'd line us up and we'd just start - ishi, ni, san, shi, go (he'd count off ten kicks at a time, in Japanese), back and forth across the room, then we'd be at 160, then 570, then 837, and 1000, and we'd go home totally exhausted but satisfied. It taught me about willpower and things that seem difficult. Just get going, that's all.

And I thought a lot about those 1000-kick sessions a few years later, on a trek in Madagascar. This was 150km across a remote peninsula, up and down hills, through forests, across rivers, and this during a nationwide uprising against the regime, with nearly all phone lines cut. I was utterly alone, two oceans away from those I loved. So much so that when I finally got to the capital Antananarivo and found a working phone and called my sister, she said, "I got married last week."

Anyway, this trek was physically the most difficult thing I had ever attempted. There were times, with my 18 kilo pack weighing on my back and my socks like sandpaper, when I'd be weeping with exhaustion, frustration and loneliness ... and yet I know, given the chance, I'd do it again in a flash. It took all I knew about willpower, and it gave me belief in myself. I owe that to Lee and his karate sessions.

4) In the late 1990s, I wrote a weekly column for rediff.com, one of the first Indian journalism efforts online. Even today, I run into people who remember me from those days, and will tell me stories about sitting with friends and discussing my latest columns, even fighting over it. For I was one of rediff's stars, and they paid me accordingly - Rs 5000 a column, up there with the best-paid columnists in the country then.

Until the day the editor called me and said, "I'm cutting you back to one column a month, at Rs 750." Do the arithmetic yourself and you can imagine my shock. "But why?" I asked. "You're saying the same damn stuff," he said. "Again and again."

A shock, yes, but a lesson I'm forever grateful for. I never took my readers for granted again. Incidentally, the editor and I are good friends and he sometimes asks me to write for him. I like friends who will speak truth to me.

5) After I moved back to India in 1992, I began working for a well-known Bombay civil engineer called Shirish Patel, in a tiny software firm he owned. Shirish and my father were long-time colleagues and friends, and I had known him as a kid. What drew me to working for him wasn't the pay or the work - it was him, the chance to spend time with a remarkable mind. I mean, he introduced me to the firm as the "software whiz from America", for I had a degree and years of experience in C, C++ and Lisp. But I soon found that the real software whiz was him. Entirely self-taught in a year or two, he was streets ahead of me as a programmer.

Over a couple of years, we worked on a large piece of software for civil engineers. It was challenging and satisfying work, but I messed up twice, in the same way. Working on my code one day, my computer crashed. Of course we knew the worth of saving files regularly and keeping backups. But being lazy, I had done neither, and I lost many days of work. When I moaned to Shirish, he said, simply, "Just write it again."

Which I did. But some months later, my computer crashed again. Despite the earlier fiasco, I had still not been saving and keeping backups. Once again, I lost many days of work.

I moaned to Shirish once more, this time saying "How can I be of any use to you like this? Shouldn't I just quit?" He was visibly angry, but not because I had screwed up again. "Stop complaining, first of all," he said. "How does that help anyone? Just go back and write it again!"

Which I did, again. But more to learn, there. He and I were less boss and employee by then, more good friends. But that didn't mean he could not be sharp with me when I needed it. He made it clear that he had no use for my moaning. But he also made it clear that he valued my work. The scolding I got was a measure of his respect for me. And that meant something. A man like that, I could go to almost any lengths for. Don't moan, just fix it: a fine life lesson.

Shirish died three months ago. I miss you, Shirish.

6) In March 2012, an out-of-town friend came to dinner. Talking of this and that, out of the blue she said "Did you know that India put a few thousand people into a concentration camp in the 1960s?" Now concentration camps were, in my mind, what Nazi Germany did during World War 2. Not India. "You're joking, right?" I asked. "Not at all," she said, and went on to give me the gist of the story that led to my book, "The Deoliwallahs".

After our war with China in 1962, we rounded up 3000 Chinese-Indians - people who "looked Chinese", that's all - mostly from our northeast, put them on a train and sent them across the country to a prison camp in Rajasthan - not so far from here, in a town called Deoli. Some of them spent up to five years in that camp. My co-author Joy was born there and spent her first four years in that camp. How many of you have heard of this episode?

I mention this today because I was astounded that I had never heard this story. I consider myself a fairly aware, informed Indian - yet how had I lived half a century in this country before I found out about this? Why is the Deoli incarceration not in our history books? Of course the story tickled my journalists' antennae, but it also underlined for me what I believe is our fundamental duty as citizens: ask questions. Never stop asking. Never.

7) I'll give you a bonus, the seventh: In 2011, I started writing a weekly column for the newspaper Mint. It was largely about mathematics, showing how fascinating it can be. Just before the pandemic, Mint was paying me Rs 45000 for each column - and while they had to cut that in 2020, they still paid me Rs 30000 per column. And I simply loved writing them.

In March last year, after 13 years and more than 400 columns, Mint's editor called to say they were discontinuing the column. It was a shock, and as you can imagine, a financial blow (again!).

But a year later, I can't tell you how glad I am that it happened. Because it gave me the chance to take stock of my life, to understand what was important to me, to think about things I really wanted to do that I had not got around to doing.

And so I'm so glad to be able to tell you that over the last few weeks, I have been immersed in a course on ornithology, in one on thinking mathematically, in a third on writing short fiction, and in learning to play the blues on a harmonica. That's right, I'm learning again. I absolutely recommend it. I absolutely love it.

And I think today, this is what I took from BITS - not a EEE degree with those 11 Cs and 4 Ds, but the idea of learning. It never ever gets boring.

Finally: in 1987, after a small success at my job, my father wrote me a letter. He had spent his career in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), rising to the top via a number of challenging and fascinating jobs. But this letter told me something of what it really meant to him. And maybe you'll see it too, and what it meant to me.

"The changes you describe, from your academic work in Pilani and Brown to that in the University of Texas, reminds me of my own civil service career. Until the early ‘60s, my performance was not much better than perfunctory. I worked hard because I wanted a reputation for efficiency, but there was little dedication. And then in 1960 I began to work for SG Barve, and continued to do so off and on till he died in 1967 or 1968. The commitment to the people’s service Barve inspired gave my effort a totally different character, impetus and persistence. I no longer cared for whether people regarded me as efficient. I bothered very little about promotion. The reward I cherished was simply the opportunity to serve effectively.

"And when I no longer cared if people regarded me highly or whether I got a promotion, both those things came."

I want to repeat that last line: "When I no longer cared if people regarded me highly or whether I got a promotion, both those things came."

So thank you, BITS Pilani. For today. But for my life.

Write a comment ...