There's a particular astronomical phenomenon that we have been observing only for the last couple of decades - and especially frequently in the last five or six years. We observe it, but we don't fully understand it.

Imagine listening to a podcast on headphones, and there's a sudden spike in volume that not just blasts through your eardrums, but blows your head off and maybe levels your city. That's the kind of phenomenon I mean, and it is actually even more - vastly more - violent. Yet we don't experience that violence at all.

That may be because when one of these phenomena happen, the signal we get is very short and detectable only by sophisticated instruments. Yet what we detect speaks of an almost unimaginably powerful release of energy in an almost unimaginably short slice of time. Which is why I mentioned the podcast with a spike above, and which is why we don't yet understand these events. What might cause such violence?

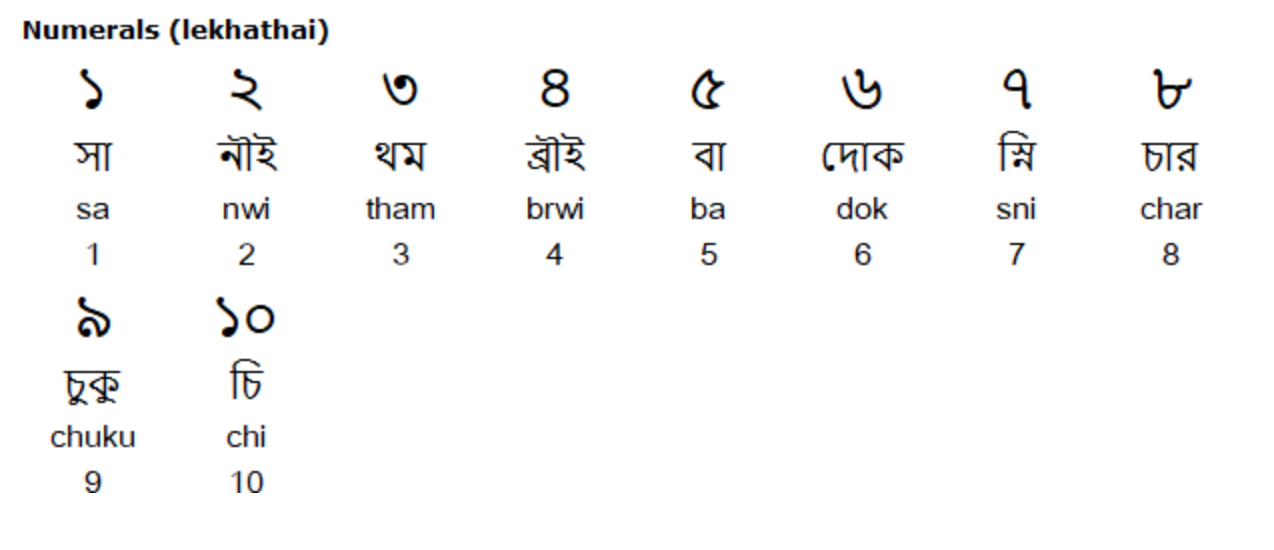

So what exactly am I talking about? What astronomers now refer to as "Fast Radio Bursts" (FRB). These are sudden spikes in radio transmission that last, on average, only a few milliseconds. Yet the reason we detect them, and are interested in them, is that they are caused by a gigantic explosion somewhere out there in the universe. What kind of cataclysm is this? In a millisecond - a thousandth of a second - an event like this releases as much energy as our Sun puts out in three days. One report I read describes them as "fleeting blasts of energy that are brighter than entire galaxies."

Now it's not as if we can see or hear these cataclysms happening. These radio bursts are almost laughably weak. Some astronomers have compared detecting them to tuning in to the signal emitted by your cellphone ... if you happened to leave it lying on the moon on your last visit there.

All this may leave you wondering. How can such a vanishingly faint signal be the signature of such an enormous explosion? For me as for plenty of others, that's both a mystery and still another reminder of the sheer vastness of space.

The mystery, because indeed, what is causing these bursts? Astronomers don't know, though they have their theories. For example, it might be white dwarfs - remnants of some kinds of stars after they have used up all their fuel - that merge with each other. Or magnetars, which are stars with incredibly powerful magnetic fields. There's also been speculation that they are signs of extraterrestrial intelligence. Whatever it is, both the speed of light and the short duration of the bursts suggest to astronomers, in ways I won't get into here, that FRB sources are likely rather small. Maybe even less than 1000km across.

So we have a small source producing a vast amount of energy. There lies the reminder.

If a train blows its horn right as it passes you, the sound may nearly deafen you, because it's that loud. But imagine it blowing its horn again when it's half a mile past you. This time, it barely registers because it's so far away - though perhaps you still hear it over the general ambient sound. In the same spirit, imagine pointing your radio telescope at a particular region of the sky where the nearest objects are millions of light years away. It detects a low buzz of radio transmissions. In fact, the telescope would detect this from any direction in the sky you point it at, for the universe has a faint but constant background hum.

But suppose now, from this particular region, your telescope also records a transmission that is maybe a thousand times "louder" than that background hum, and lasts only a few milliseconds. Because it is so "loud", you realize that if it had happened in your vicinity, it would be, well, cataclysmic. Yet what's recorded is, as I mentioned above, like the signal from your phone if it was abandoned on the moon.

You'd wonder, what do we have here? An enormous blast caused this FRB - that's why it is so much "louder" than the usual radio static. But by the time the "sound" of this blast reaches us here on Earth, it has been whittled down to a mere whisper. That speaks of how incredibly far away the blast was. FRBs in a nutshell, right there. Astronomers first detected one in 2007, by looking at data that had been recorded in 2001. By now, we have recorded hundreds of FRBs, including one that repeats every 16.35 days.

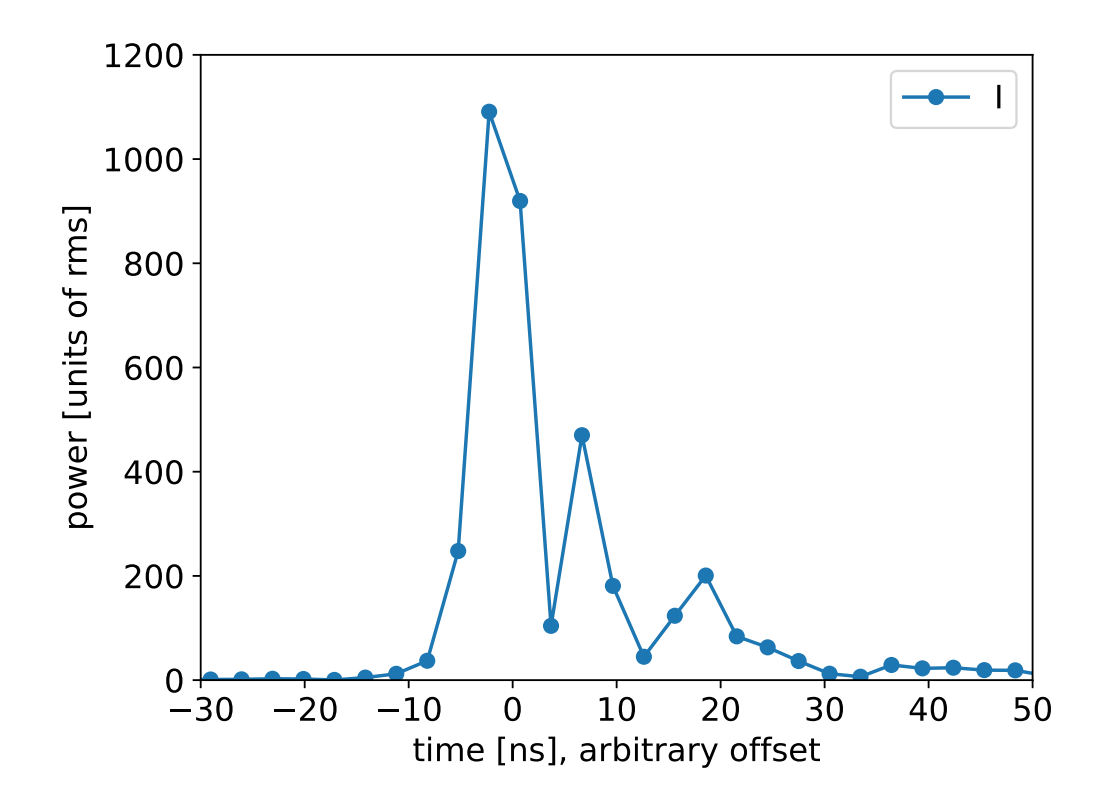

All of which may be an overly long introduction to what really prompted this article: a burst detected in June 2024 by an Australian radio telescope, the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP). This emission was remarkable even by FRB standards. It lasted just 30 nanoseconds, a hundred-thousand times shorter than other FRBs. It was also so powerful that in that minuscule slice of time, it drowned out every other signal in the sky.

What had caused this unusually brief, but unusually strong FRB? Well, a year later, a team of scientists published a paper answering that question (CW James et al, A nanosecond-duration radio pulse originating from the defunct Relay 2 satellite, 16 June 2025). It begins thus: "We report the detection of a burst of emission [by] ASKAP. The burst was localised" ... to where?

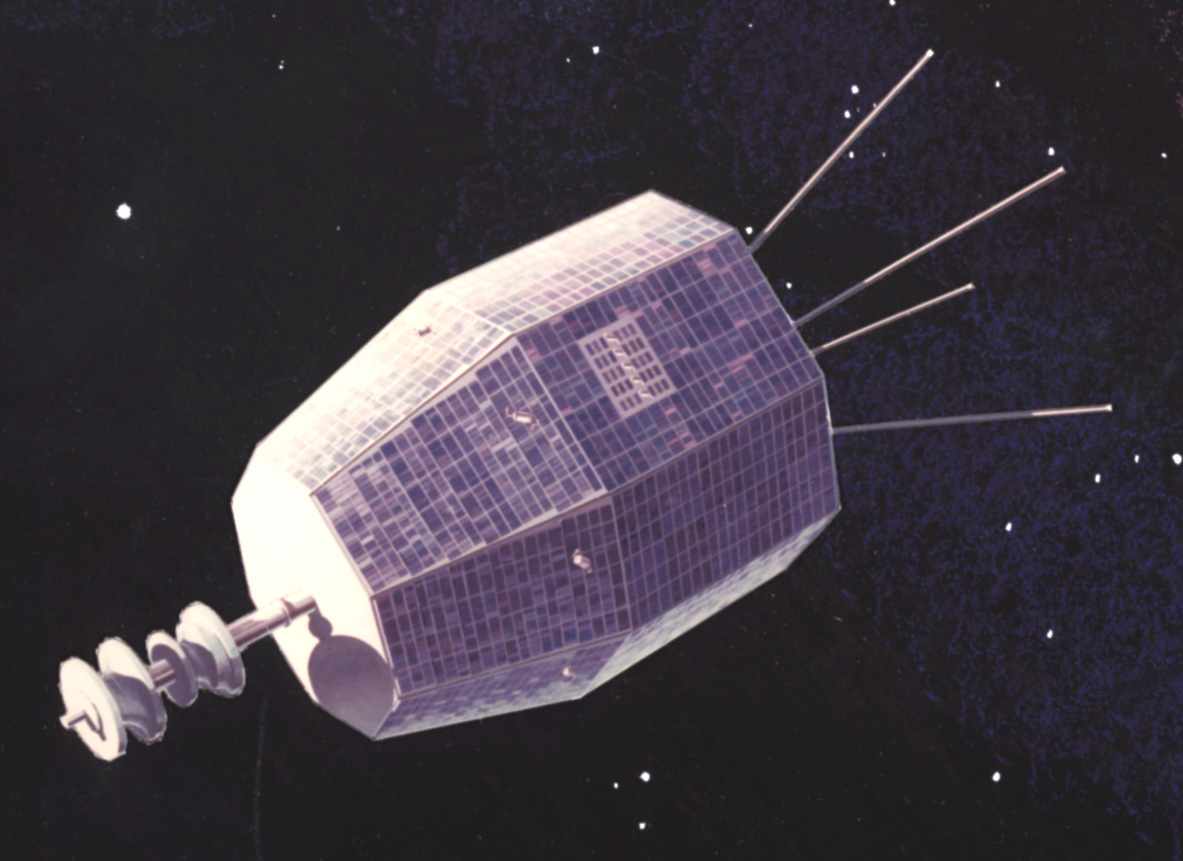

"... to the long-decommissioned Relay 2 satellite."

That's right. Relay 2 was launched in 1964, but had totally failed by 1967. For nearly 60 years, it's been just another piece of space junk orbiting the Earth. So what caused that particular burst wasn't a cataclysm, but a sudden transmission from a dead satellite that ASKAP caught because it just happened to be pointed in that direction; a "serendipitous detection", the scientists write.

But if this burst wasn't a FRB like all the others, we still have the same question: what caused it? Again, scientists don't have a satisfactory answer. It certainly wasn't the satellite itself, whose systems have been dead since 1967. The paper suggests two explanations. One, an electrostatic discharge, similar to the slight shock you get from a sweater or a carpet. Two, a tiny fleck of space dust - a micrometeoroid - zooming through space at 70,000 kmph hit the satellite.

That's fast. But how tiny? "[A] 22µg micrometeoroid could produce the observed field strength for our burst", write the scientists. That's 22 millionths of a gram. That is, 45,000 such micrometeoroids would make one gram.

So: FRBs might originate millions of light years away, caused by an explosion that would overwhelm our Sun. They are only a few milliseconds long. But then astronomers detect a pseudo-FRB that's thousands of times shorter still. Turns out it might have been caused by a bit of space dust that weighs a few micrograms, barreling into a long-kaput satellite at a speed we humans can only dream of.

I tell you, everything about this story is a treat. Astronomy itself is a treat.

Write a comment ...