(So this is a followup of sorts to my previous column in this space - I wrote it as my regular contribution to 3 Quarks Daily.)

The star Proxima Centauri has been in the news this August. One reason is actually as a sort of corollary, a side mention. Proxima Centauri, Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B are the stars that make up the star system we know as Alpha Centauri: a triple star system, though without a telescope, we see it as one star.

Now such a system is fascinating enough by itself, but the real reason Alpha Centauri interests us Earth folks is that it is the closest "star" to us apart from our Sun - about 4.5 light years away. And of the three, Proxima Centauri is actually the closest. And, as a red dwarf, it's the smallest, the coolest, the ... in fact, deadest of the three. That's because red dwarf stars are close to the end of their lives.

This August, a team of astronomers used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to discover a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri A. Not only that, it looks like the planet is in Alpha Centauri A's "habitable zone", meaning it's at least possible there might be life there. (See my The mask does a job.)

Why is the Alpha Centauri A planet a reminder of Proxima Centauri? Because while this planet is new to us, we've known for a few years now that three planets orbit Proxima. Which means that of the nearly six thousand so-called "exoplanets" - planets outside our Solar System - we know of today, these three are the closest to us. What's more, one of them is in Proxima's habitable zone. (That particular exoplanet prompted this column, but it returns only near the end.)

It should be no surprise that there are scientists who put those facts together and think: Can we humans get there? Can we live there?

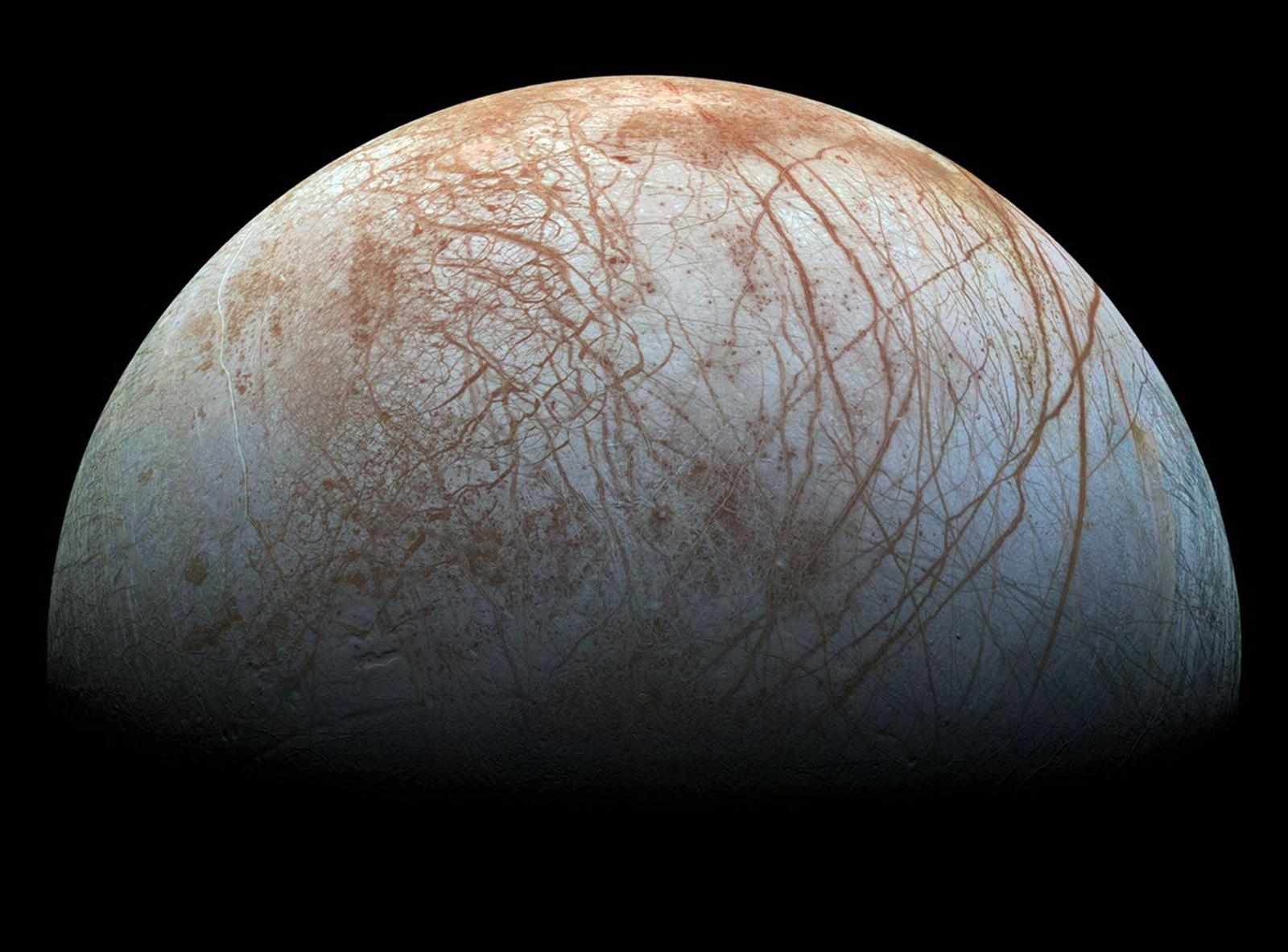

The second of those questions is the harder one to answer, because how do we assess conditions on a world that far away? Then again, we all know how seriously humans are taking the possibility of living on Mars, and working towards that goal. What's more, Mars is not the only body in our Solar System we are looking at with this kind of interest. There's also Europa, one of Jupiter's eighty (!) moons. For various reasons, scientists have long believed it's the most likely place in the Solar System we'll find life, if you discount life on Earth, that is. Similarly, they also believe it might just be a habitable place for humans.

So why not send a mission to Europa? Well, there's the "astrobiology" mission Europa Lander that was first proposed about twenty years ago. It keeps getting pushed back: 2023, 2025, 2030, who knows when it will happen. But if it does launch one of these years, it will eventually land on Europa and search for signs of life. Remember that we want to conduct such a search because it seems possible to us, from 600 million km away, that life might exist there.

Must keep that distance in mind. For by any planetary standards, both Mars and Europa are eye-wateringly far away. A mission to Mars will take about 8-9 months; to Europa, about 5-7 years. Long journeys both, but you can at least imagine humans going to either place and even returning.

Yet compared to these two, Alpha Centauri is unimaginably distant - and remember that even so, it's the closest star system to us. In fact, Alpha Centauri helps me in trying to grasp the vastness of this universe we inhabit. If the distance between a pair of celestial objects makes you gasp, remember there's always another pair whose separation makes that distance seem infinitesimal by comparison. In this case, Europa is 600 million km from us, but Alpha Centauri is nearly 70,000 times further, or 40 trillion km away. But it's easy to make that 40 trillion seem infinitesimal in turn. Consider Andromeda, the nearest major galaxy to us. It's nearly 600,000 times the distance to Alpha Centauri. (I'll spare you the number of kilometres.)

And so it goes.

So yes, we don't know if humans can live on exoplanets like those in the Alpha Centauri system, and that's partly because it is so distant that we can't assess conditions there. But we do have some idea how long such interstellar journeys will take. That's at the heart of a fascinating competition, Project Hyperion, that recently declared its results. Entries had to "explore the feasibility of crewed interstellar travel via generation ships, using current and near-future technologies. A generation ship is a hypothetical spacecraft designed for long-duration interstellar travel, where the journey may take centuries to complete."

Centuries - because it will indeed take at least centuries for a spaceship to reach an exoplanet. And of course, the plan has got to be to reach an exoplanet. What would be the sense of reaching a star that will only devour the ship and everyone in it?

Project Hyperion specified that entries needed to come from teams that included "architectural designers, engineers, and social scientists". After all, the initial crew on the ship will die en route, and it will be their probably distant descendants who finally reach the destination. So the ship has to be able to sustain a large enough number of people, in effect allowing them to "function as a closed society over centuries." Just thinking about this raises all kinds of complex issues, and that explains the need for a multidisciplinary team.

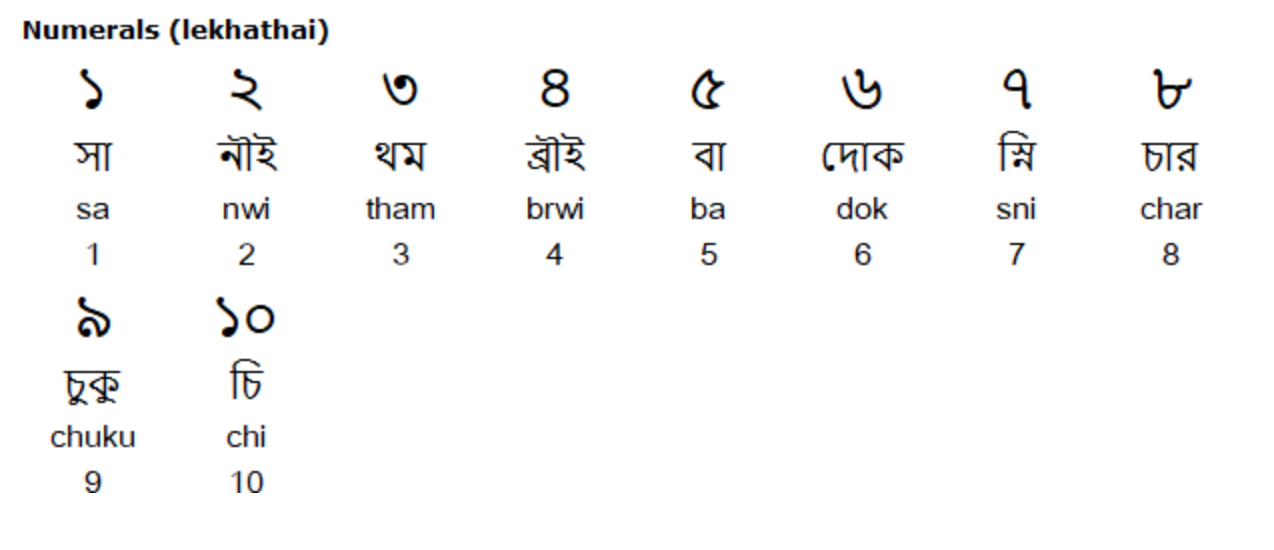

Five Italians won Hyperion's first prize with their design for a spaceship they call "Chrysalis". There's an architect, an environmental engineer, an economist, an astrophysicist and a psychologist who is also an actress: hard to get more multidisciplinary than that. They envisage Chrysalis taking up to 2400 people, over 400 years, to Proxima Centauri b, the exoplanet that orbits Proxima Centauri.

It's absolutely worth reading through their detailed proposal. But here are just a few snapshots from it, to offer a flavour of what the Italians had in mind:

* Chrysalis will be a tapered cylinder, 6km across at one end, 58km long.

* It will be built entirely in space, at the Lagrangian point L1, about 1.5 million km from Earth. Team Chrysalis believes it can be built in 25 years starting now. (JWST is stationed at Lagrangian point L2.)

* The "initial generations" on this mission will spend 70-80 years in Antarctica, to adapt to an "isolated environment".

* Food will be grown and produced on the ship. The diet will be "essentially vegetarian", though there will be some animals on board "for diversity and aesthetic purposes."

* There will be an annual "Chrysalis Plenary Council", seeking to maintain "a sense of unity and harmony among the inhabitants."

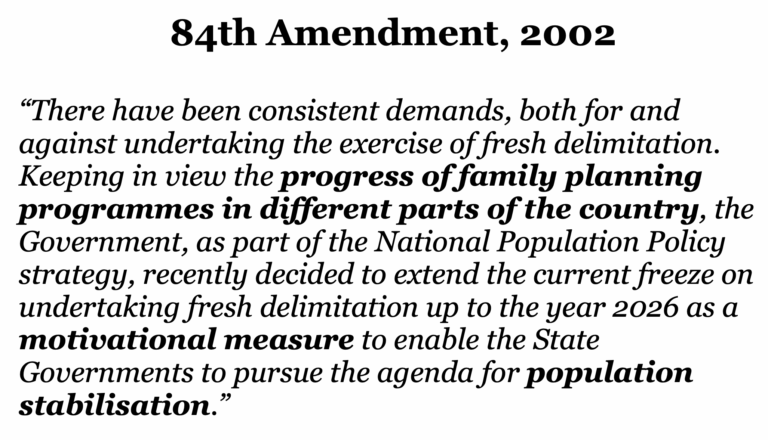

* There is a real risk of "possible overpopulation or total extinction of the population" on the ship. So births will be planned: "each inhabitant will generate at maximum 2 children, not necessarily with the same partner." For the same reason, voluntary euthanasia is a consideration.

Chrysalis has plenty more that got me thinking. Will it ever be a reality? That is, will humans ever get to Proxima Centauri b, or some other exoplanet? Well, a century ago we might have asked the same question about going to the Moon. A little over half a century ago, we answered it.

Me, I'll hold on to that.

Write a comment ...