There's news and trumpeting, as there seems to be every few years, about India's Total Fertility Rate, or TFR. And that means another opportunity to examine both the TFR and what it means for our population growth.

But what's TFR? It is defined as the average number of children born to a woman through her life - or, more accurately, her child-bearing years. As you might guess, the rate of growth of a country's population is intimately connected to its TFR: the higher the TFR, the faster the population grows. As you might also guess, TFRs change as a country "develops" - meaning as its population gets wealthier and more educated. It's no secret that women in such countries have fewer children than those in poorer countries, and the change in TFR reflects that. The world over, more "developed" countries tend to have lower TFRs than less "developed" ones. This is why the populations of richer countries grow more slowly than those of poorer countries, or even decline.

Note that immigration skews this broad-stroke picture, but let's leave aside that consideration for now.

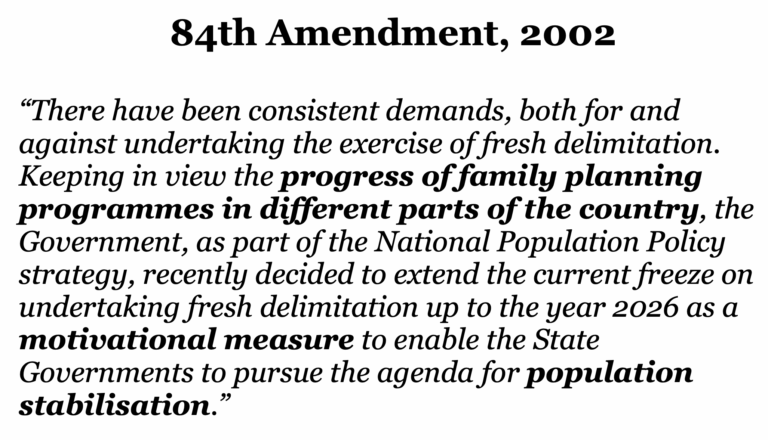

One more thing to note about the TFR. A value of 2 is considered "replacement level". That's because it means that couples produce 2 babies each, precisely replacing themselves; it also means that when the TFR is at 2, populations will eventually stop growing. In the real world though, some babies die. So replacement level is usually understood as 2.1. This number is something of a holy grail for developing countries. Getting there is not just a sign that your population growth is under control. It also suggests - if broad-stroked again - rising levels of education and prosperity.

And this is why the recent interest in India's TFR. Only a few days ago, we read that India's Office of the Registrar General (which uses the unfortunate acronym ORGI) has released their Sample Registration Survey Statistical Report for 2023 (available for download here).

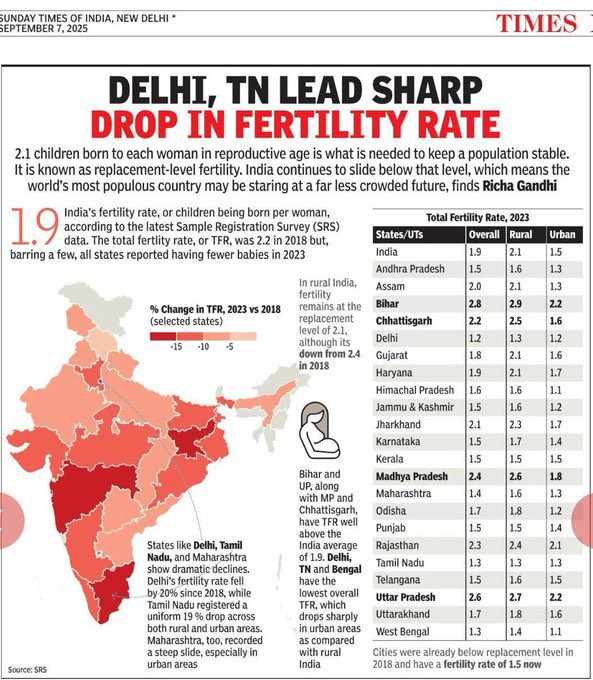

Worth noting in this Report was that the country's TFR had declined in 2023 to 1.9, or below replacement level. News about the Report variously noted that India's TFR was 2.2 in 2018, and had "remained constant at 2.0" in 2021 and 2022, meaning it "had fallen for the first time in two years." (For example, this report.)

In addition, the Times of India reported that "barring a few, all states reported having fewer babies in 2023" (see image above) - which, I assume we should infer, is the fallout of the drop in TFR from 2.0 in 2022 to 1.9 in 2023.

The implication in all this, of course, is that the development path India has chosen is taking us to that promised land where women are educated, where we are all relatively prosperous. Thus we'll emulate other countries that have seen their populations stabilize and decline. The Times of India said it explicitly: "The world's most populous country may be staring at a far less crowded future."

Yet as ever with figures, it's worth examining them a little more closely. For example, since the Times graphic mentions them, let's consider babies. The Report above does not tell us how many babies were born in 2023, statewise. But I got my hands on a 2022 ORGI Report, "VITAL STATISTICS OF INDIA BASED ON THE CIVIL REGISTRATION SYSTEM" (available here). In it, page 35 carries a table titled "Number of registered births by States/Union Territories, 2013-2022."

Looking at this table, you will see that barring a few, all states reported having more babies in 2022 than in 2021. (The exceptions are Bihar, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, West Bengal and the Union Territories of Ladakh and Lakshadweep.) Is it possible that in one year, this situation changed enough so that we can claim the opposite: "barring a few, all states reported having fewer babies in 2023"?

In a word, no. Much like large ships that don't change course quickly, large populations simply cannot and do not change character that quickly. If their counts are growing, they are not likely to suddenly drop. If they are producing more babies year-on-year, they are not likely to suddenly produce less the next year. If startling changes like those do actually happen, there is invariably an unusual cause: maybe a pandemic, maybe a war.

But we do have an unusual cause here, you might say: the drop in the TFR. Well, to start with, going from 2 to 1.9 is not much of a drop. Nor is it unusual. More to the point, a drop in the TFR cannot have an impact that quickly. To fully understand this, we'd need to study the age structure of India's population, look at fertility rates and mortality across ages, get an idea of how many women of child-bearing age there are and how many of them have already had babies, and much more - and then we'd need to track this data over time. This is a complex task that accomplished demographers build models for. Beyond me, for sure.

But let me give you an idea of one aspect of this model. The striking thing about India's population is that it is young. The median age in this country is about 28, meaning half of India is younger than that. This is our great demographic advantage, of course. Remember then that child-bearing is also largely the domain of the young. Meaning, we have a huge number of people who are in their child-bearing years, and that will remain true for a long time. Our demographic advantage also gives us a certain baby-producing momentum, therefore, that is hard to slow or stop. No matter that our TFR has sunk from 2 to 1.9.

Yet what we can indeed infer from that drop is that the growth of our population is slowing. But the population itself will keep growing for many more years. Eventually it will level off and then start falling. When will that happen? Last year, for example, the UN projected that India's population will rise to a peak of about 1.7 billion in the 2060s, and only then begin a decline.

40 more years of growth, says the UN. Not likely if most of our states had fewer babies in 2023. Add to that ... well, how long after the 2060s, do you think, it will take us to sink from a 1.7 billion peak then, to far less than today's 1.4 billion? That's when we'll be "far less crowded" than today.

And if that future is plenty more than 40 years away, I'm not sure we're "staring" at it.

PS: What actually might have been true about "barring a few, all states" is that they reported a decline in their TFRs in 2023 (Table 15, page 314 in the SRS Statistical Report above). But by no means does that equate to "having fewer babies in 2023."

Write a comment ...